Childcare expenses account for 8% to 19% of family income per child and present barriers to employment for many parents, according to a new, county-level database of childcare prices the U.S. Labor Department released in January.

Because millwrights and other tradespeople often work non-traditional hours and travel long distances to jobsites, typical childcare-center hours add another layer of difficulty for workers in these careers, which can provide a pathway to the middle class. Many millwrights have to enlist not just one childcare center but two or three resources to accommodate their schedules, making care even more expensive, said Sarah Jones, a member of Millwright Local 2232 and co-chair of the SSMRC Sisters in the Brotherhood Committee.

“I know of no daycare that would provide childcare for the month-long, 14-hours-a-day, 7-days-a-week job that I just got called to take,” said Sasha Norris, a single parent and millwright apprentice with Local 1263. “Even if I could put two children in daycare, then paid someone to watch them the few hours before the daycare opened and a few hours after plus take them to the daycare and pick them up, I would not make enough to pay the daycare and sitter after paying for rent, gas, and food.”

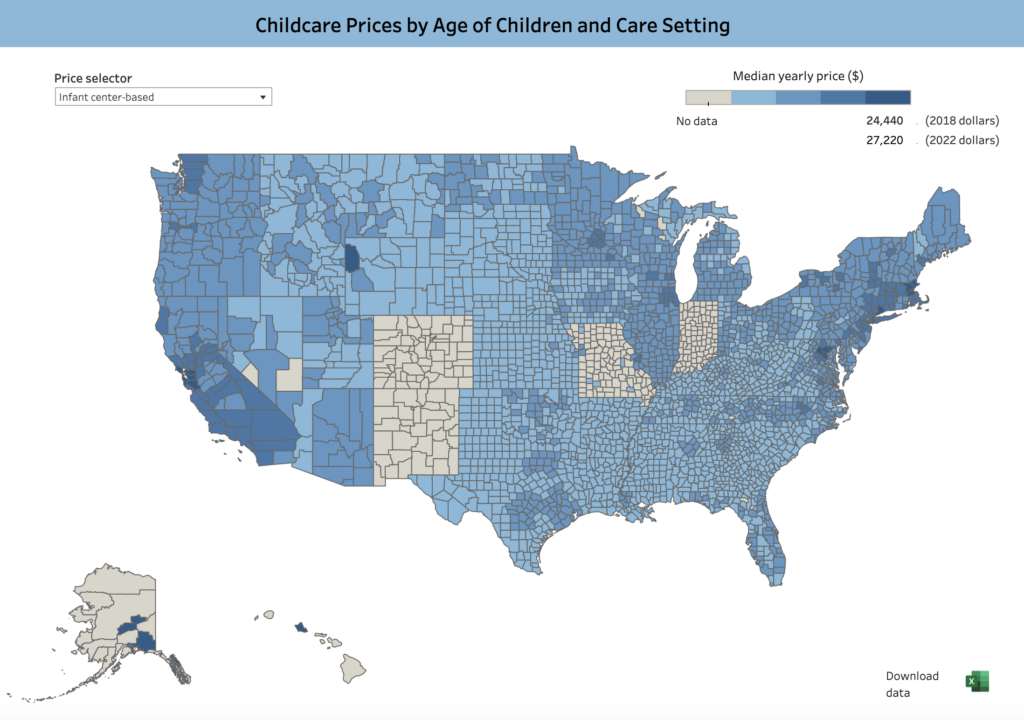

The National Database of Childcare Prices gives childcare price data by provider type, age of child, and county characteristics, including median family income. It contains data from 2008 to 2018. According to the Labor Department, the database fills a knowledge gap because most other sources of childcare-expense data give prices at the national or state level, and prices can vary significantly within states and local areas. Click the map below to view numbers by county.

Childcare prices range from a low of $4,810 ($5,357 in 2022 dollars) annually for home-based care of a school-age child in counties with small populations to a high of $15,417 ($17,171 in 2022 dollars) for center-based care of an infant in very large counties.

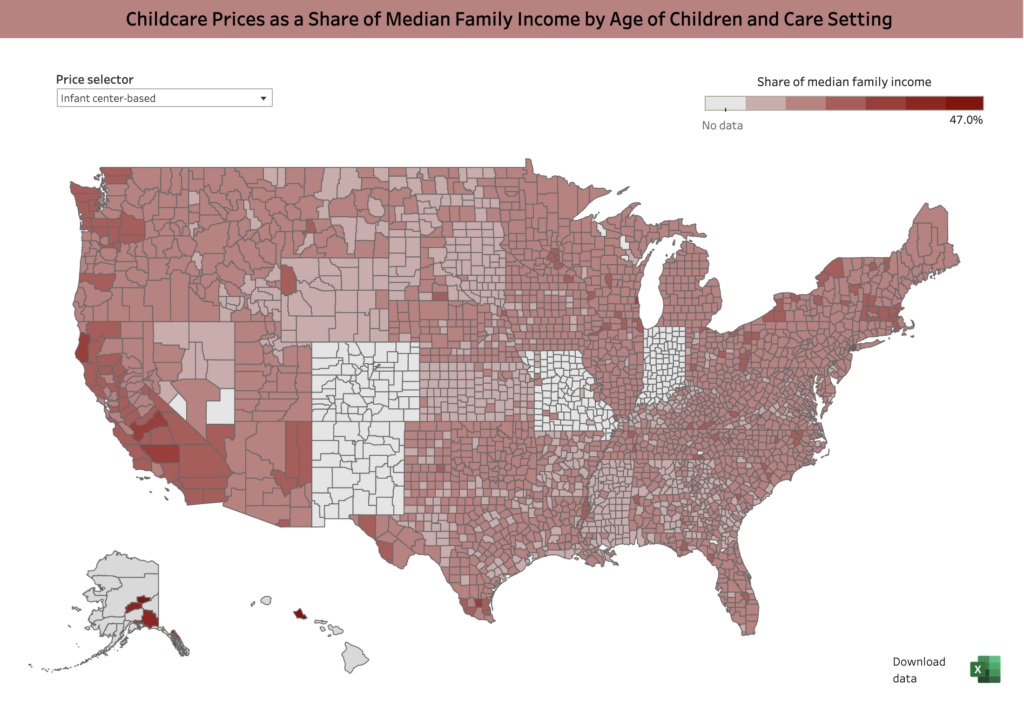

“As a share of family income, the NDCP shows that childcare prices are untenable for families across all care types, age groups, and county population sizes,” states a DOL Women’s Bureau report about the database.

Norris agrees. “Basically, the childcare barriers make it impossible for a single parent without assistance from friends or family to better their lives with an opportunity to have a good career in many trades,” she said.

Click the map below to see childcare prices as a portion of median family income in various counties.

Here are key points from the report on Initial Findings from the National Database of Childcare Prices:

- Even for a single child, childcare consumed a significant percentage of median family income; many families pay for care for multiple children, compounding the burden.

- Housing typically represents the largest expense for families. However, families with multiple young children spend more on childcare than housing when they pay for care.

- Single-parent and single-earner households, as well as those with income below the county median, are less likely to have affordable childcare. In 2021, infant care prices across U.S. states were equivalent to 24.6% to 75.1% of family income for single-parent households.

- Families with higher income levels spend more on child care, but it makes up a smaller share of their income.

- Compared with other high-wage countries, the United States government spends little on early care and education. Out of 37 ranked Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, the United States ranks 35th on expenditures for early care and education for 0-5 year olds.

- Higher childcare prices depress maternal employment. Conversely, an expansive review of the literature shows that a 10% reduction in childcare prices for care of young children is associated with an increase in maternal employment ranging from 0.25% to 11%. The NDCP shows that counties that had more expensive childcare prices had lower rates of maternal employment.

- Mothers living in states with more expensive child care and less generous subsidies and publicly funded childcare programs are less likely to be employed after having children.

- Childcare was consistently more expensive for younger children as care for younger children requires a lower caregiver-to-child ratio to meet children’s needs.