More than 1,000 feet underground, there was a problem inside Alabama’s largest coal mine. Material was free falling 8 to 15 feet at transfer points in the mine’s conveyor system, damaging the conveyor equipment. Power Techniques Inc., a contractor specializing in bulk material-handling equipment, had a solution – a proprietary transfer system designed in South Africa and manufactured in Kentucky – and in spring of 2021 Southern States Millwrights helped the company install three massive chutes comprised of 6 tons of steel.

“Peabody Energy, the mine’s owner, wanted a transfer chute that would move the material from conveyor to conveyor in a better manner,” said Cary Henken, president of Power Techniques. “Our controlled-flow chute basically takes the material from one conveyor to the other like a water slide. It eliminates impact and loads material to the outgoing conveyor at the same speed it’s coming off the incoming conveyor.” The design also reduces the amount of coal dust in the air, which lowers the risk of explosions.

Shoal Creek Mine stretches under three counties and a river and is up to 1,300 feet deep. Members of Southern States Millwright Regional Council don’t typically work in mines, but Local 1192 mobilized quickly to staff the project and provide members with the training required to work underground.

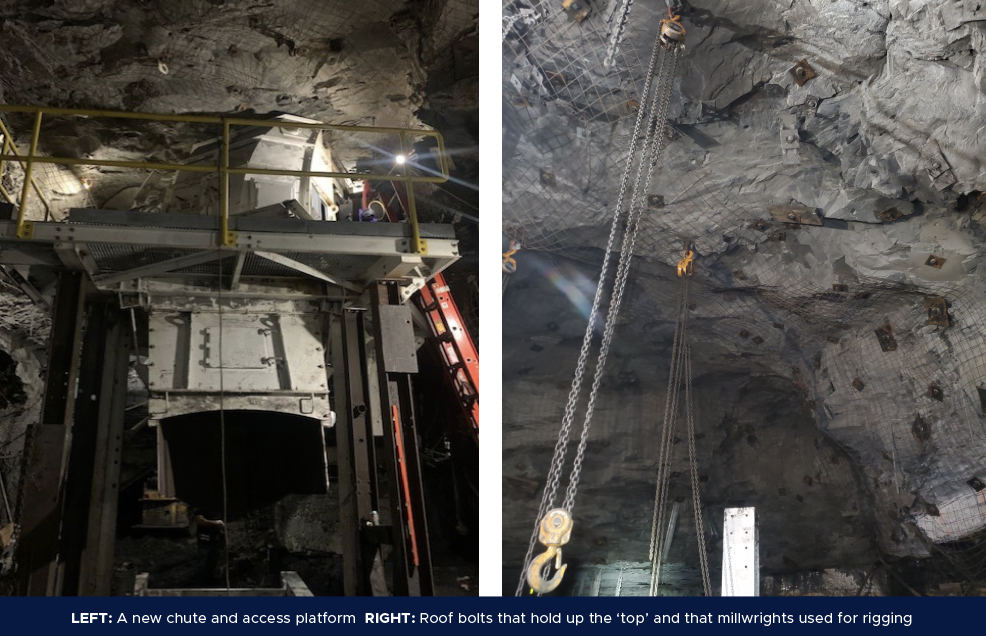

Nine millwrights completed the project in eight weeks, ending in June. Their work involved demolishing existing systems as well as installing the new chutes, moving head pulleys, adding steel framework, replacing chromium liners, and building a new cat-walk system.

“It was great to see the job with Power Techniques be successful and completed safely,” said Clint Smith, business agent for Local 1192. “I’m glad our members were able to work in a totally new industry to us, and I believe they did an outstanding job.”

1,200 feet down

Working so far below ground is not for everyone, said Joey Rakestraw, a member of Local 1192, but he enjoyed it. “It’s pretty amazing how it’s set up,” he said. “You drop in a big elevator – it takes about 7 minutes. Then they have these military, Humvee-style vehicles that you drive to where you’re working in the mine. There are a lot of facilities down there, like shops where they work on their equipment.”

Conveyors stretch the length of the mine, and one work area was about 5 miles from the elevator shaft, Rakestraw said.

Millwrights took a 32-hour Mine Safety and Health Administration course before beginning work. “It’s a four-day class, and then you do your fifth day at the mine,” Rakestraw said. “They give you a lot of information about things that have happened in mines and the dangers. You have to watch out for yourself and make good decisions. The mine is pretty safe. But if you’re not paying attention, you could get in trouble real quick.”

Power Techniques, based in Alma, Illinois, performs a lot of work in underground mines in the northern United States, and the company provided an experienced foreman and supervisor to lead the crew. “We had to make sure guys were comfortable going underground, but everything went well,” Henken said.

Rakestraw has primarily worked in automotive plants, and he said his skills translated well to the underground conveyor systems. “I’m very good with fabrication and torching and layouts,” he said. “The majority of what I did was rigging, cutting, welding, and layout for adding new steel to existing steel,” he said. “We had a lot of precise layouts to do there.”

Equipment operation and rigging

Because the mine was closed during the project and no equipment operators were present, millwrights had to learn to operate loaders and other machines used to transport the large pieces of steel they were removing and installing. “They had to task train our guys on the equipment and we had to run it all,” Henken said. “The millwrights had to become operators.”

The equipment signaling system used in mines is completely different from the one used on the surface, Rakestraw said. “We’re used to using hand signals, but they use the lights on their helmets,” he said. “They’ll swirl their head in circles or swipe the light left or right.”

Rigging underground was different as well. Instead of using cranes, millwrights had to construct rigging systems using the roof bolts in the mine’s ceiling, which is called the “top.” Placed every 5 feet, the roof bolts are up-to-16-foot-long anchors that are drilled into bedrock and hold up the top. “We had to learn to trust the lugs that were in the ceiling,” Rakestraw said.

Demolition

Millwrights demolished existing chutes, which were like square boxes and did nothing to control the material’s fall. They then had to adapt the remaining conveyor system to work with the new chutes.

“It was quite a large demo,” Rakestraw said. “It took one week of two shifts with plasma cutters and torches. Sometimes we got 20,000 pounds of steel out of one area in a shift.” Millwrights performed work in three different areas of the mine.

In the humid environment of the mine, the old chutes wore out quickly and were often shored up with heavy-duty, 1-inch-thick, abrasion-resistant steel plate. “You can imagine, after 15 to 20 years of them plating and patching and fixing this chute, what it was like,” Rakestraw said. “And there’s no taking old bolts out because they’re so badly rusted that you just have to cut them.”

Preparing the remaining steel to connect with the chutes presented challenges, too. “The existing material that’s down there has been there so long it’s rusting and it’s flaking off, so you have to really clean it and air hammer the old rust off to get it down to where you can actually work with it,” Rakestraw said.

Assembling the chutes

“These are 72-inch-wide conveyors, so these chutes are huge,” Henken said. “A cow could walk through them. They’re big and heavy.”

Due to the size and weight of the new chutes, they couldn’t be assembled and then moved into place. “You have to build it in sections and install it basically from the top down,” Rakestraw said. Even the smallest sections are big, heavy, and awkwardly shaped, making them difficult to maneuver. “You can’t really just grab the stuff,” Rakestraw said. “You have to use a come-along.”

Millwrights both welded and bolted the sections together and to existing pieces.

With one of the chute installations, the new system was so different from the old one that the head pulley had to be moved forward 8 feet and up 10 inches. “We had to weld guides on it, and we had to add some steel frame, and then we put 6-ton come-alongs on each side of it,” Rakestraw said. “On top of our new steel, we put a layer of grease, and we just kind of drug it across that grease because it’s really big. It was 20,000 to 30,000 pounds. We normally use a crane. There was no way to do that, so we had to come up with a plan. It was quite an ordeal.”

Contractor relationship

While the Shoal Creek Mine project was the first in which SSMRC millwrights worked with Power Techniques underground, the two organizations have teamed up several times before. Tennessee Valley Authority locations where Power Techniques has partnered with the SSMRC include Widow’s Creek Fossil Plant in Guntersville, Alabama, Colbert Fossil Plant in Tuscumbia, Alabama, and Kingston Fossil Plant near Kingston, Tennessee.

Rakestraw said the Power Techniques staff members who worked with the crew at Shoal Creek Mine were very knowledgeable. “One of the guys was a mining engineer,” he said. “We didn’t know some things, and we could always ask them. They knew what they were doing, and they took care of us very well. I would love to work for Power Techniques again.”

Future work

Smith said Local 1192 looks forward to more collaboration with Power Techniques. Peabody Energy plans to install three more chutes at Shoal Creek Mine, Henken said, and the company has discussed the possibility of Power Techniques providing a full-time maintenance crew. Henken said millwrights from the SSMRC would fill those positions. “We’re going to be looking for local hands that live in the area to do work,” he said. “We’ll give them the tools and everything they need to do their jobs.”

Rakestraw likely would be first in line. “It would be awesome if we could get some steady work with them,” he said. “I really enjoy the tough, dirty, cutting, welding, big-rigging type of jobs. If it’s a challenge, I do well at it. And trust me, it’s a challenge, from start to finish, just to be down there. I didn’t want to leave.”